Achieving supply chain predictability is a competitive advantage for most manufacturers. Each year, business planning models are filled with assumptions of their manufacturing network’s capability to produce and ship product as promised to their customer base. These assumptions are often very conservative and based on history of less than optimum performance in many cases. Manufacturers need to understand their current capabilities and to continually improve their reliability strategy and process availability.

Traditionally, the capabilities of these facilities in their networks vary as a result of product mix, processing, packaging capabilities, shipping issues, access to markets, distribution networks, and the availability (uptime) of their assets. However, many uptime issues are caused by unreliability which are the result of equipment failures, process and operational issues. Reliability is defined as the probability that the equipment will perform its intended function when required. Manufacturers strive to improve reliability in order to have predictable supply chain processes which deliver product to customers on time meeting all “purchased” specifications.

Some manufacturers drive a strategic approach of how to improve their manufacturing network (site) availability through providing corporate reliability guidance. However, this is not the common approach to improving the maintenance strategies of the manufacturing supply chain. Many allow their sites to develop their own practices which may not reflect best practice and often compete (and lose) to other corporate initiatives. The purpose of this article is to provide a five-step process to developing a corporate reliability strategy.

There are several factors leading to the success of a corporate maintenance strategies such as:

- Leadership – driving the initiative both from a corporate and business position

- Strategy – targeting what the business needs to survive

- Structure – including the “right” elements

- Culture – collaborating, focusing on defect elimination, and being proactive

- Talent – supporting its implementation

- “Buy-in” from participants – accepting the initiative from the board room to the production floor

- Competency – obtaining knowledge of practices

I will discuss how these corporate reliability programs can enable the over-arching business goals to improve supply chain capability, capacity and predictability.

Why Develop a Corporate Reliability Strategy? The Value Proposition

The value proposition for a corporate reliability strategy can cover many aspects important to the business. The evaluation begins with what is “plaguing” the business currently followed by future needs that will met with this comprehensive equipment care initiative. The development of the value proposition starts with company and business leadership as they begin to understand the potential case for improving asset care.

Reducing the impact of consequences from environmental, health, and safety incidents from equipment failures leads our value proposition list. Undesirable potential impact of these events to the community and employees. Second, unplanned events can upset network capacity and cause customers to miss their orders.

Gaining manufacturing network capacity by improving plant uptime can defer capital investment can also be an objective of a corporate reliability strategy. Especially for manufacturers that requires multiple manufacturing locations from products with short shelf life, high shipping costs, and the need for geographic locations to markets. Gaining a fraction of the uptime from several facilities can negate the need to build new facilities saving millions in capital investment.

Many companies confuse the primary purpose of deploying corporate reliability programs with the need to standardize the response to maintenance and reliability issues. Although the response to failure is necessary given the impact of the response to the individual plant budget, the primary justification must be tied to enabling the mission of the business. Failure to measure the initiative’s impact at business-level objectives will lead to a “program-of-the-month” which can be eliminated by senior leadership at a later time.

Case studies have shown that “defect elimination” cultures enable improvements justified by corporate reliability strategy. The endorsement of senior leaders for deploying a corporate reliability strategy will drive the creation of the needed “defect elimination” culture. The establishment of a reliability policy (discussed later in this article) will drive a similar response that we see in the approach to safety, quality, ethics, and environmental policies.

Other factors included in the value proposition are:

- Focusing the organization on business goals and objectives

- Gaining a more predictable supply chain

- Reducing overall operating costs through reductions in breakdowns

Certainly, all these factors lead to improving “bottom line” results from sales revenue improvement, higher margins and lower operating costs.

Overview Corporate Reliability Strategy Process

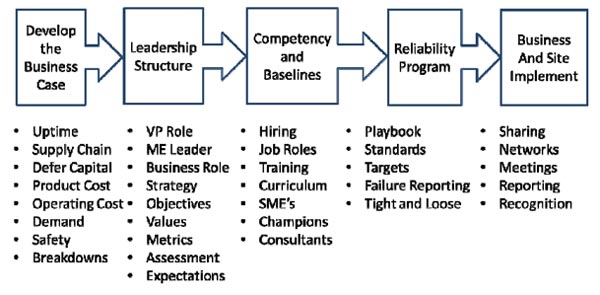

This article follows the above process for developing a corporate reliability strategy. It is based upon the experience of several companies as they deployed their initiative. A company can start this process in any step depending on their progress with their response to caring for their equipment.

The process begins with Senior company and business leadership developing the business case they will use to “sell” it to the organization. This assumes a fairly enlightened leadership that understand the potential benefit for the application of maintenance and reliability practices. In some cases, leadership gains knowledge through conferences and case studies from other companies in their industry.

This is followed by developing the structure and foundation elements needed to drive the initiative out of the gate. Certain roles will need to have responsibilities added to their portfolio and others will need to be hired or promoted into roles such as global reliability leader. Within this step is the development of the vision, values, and strategy that will carry this initiative to the ground floor. Before any work get started, metrics are needed to gage long-term progress. These are high level lagging metrics to be reviewed by leadership quarter to quarter. The corporation also needs to know where each site is starting from with implementing the initiative. Assessment either self-executed or by a third-party will dictate what each site will focus on to achieve the targets of the high-level metrics.

Ensuring the organization has the knowledge, competencies and skills to properly deploy the maintenance strategy is the next step in this process. Every aspect from hiring, job descriptions, job promotion, incentives, and training needs to be reviewed and adjusted. Training must be customized for each organizational levels. Leadership will need training on reliability, machine failure, and establishing the business case while floor-level personnel must be involved in learning troubleshooting and root cause analysis skills. “Who does what” is answered across the roles of subject matter experts, champions, and consultants.

“Developing the reliability” program step involves establishing the playbook by standardizing and writing out the methods and tools each site will use in this initiative. The playbook can be organized by several means as body of knowledge pillars, work processes, and selected tools and methods. Failure reporting is also started in order to accelerate the remediation of bad actors across the network. A useful strategy is “loose and tight” which allows for both corporate guidance and site flexibility to use site developed methods. This strategy is useful in allowing their mature practices and not have practices dictated to them by sites that are not known for their reliability efforts.

The last step in this overview of the corporate reliability strategy development process is implementing the initiatives across the network through sharing results and leveraging network to “pollenate” all sites in best practices. These efforts should be supported by regular reporting of metrics and company meetings to assess progress, share results, and celebrate achievement of targets. All this progress is enabled through recognition both in individual’s career paths through promotional opportunities and individual achievement.

Develop the Business Case

Guidance for improvement of reliability exists in many forms. Companies can “do nothing” and allow sites to develop “pockets of excellence” but these efforts succumb to people changing roles and momentum can be lost. Senior leaders can provide verbal support during visits, but their advice can be ignored after they leave like” driving past the speed trap.” Unfortunately, this can also lead to confusion from various interpretations of what was heard. More effective guidance is through a structured program built upon a strong business case. The business case should focus on remediating what has plagued the business in the past and what the future focus should on in response to market conditions. The business case can focus on these issues:

- Uptime

- Supply Chain

- Defer Capital

- Product Cost

- Operating Cost

- Demand

- Safety

- Breakdowns

Typically, the business case for reliability centered maintenance must be “sold” at the highest level in the company since top-down support is it lifeline. At the senior level in the company it is decided what will be delivered as a corporate reliability strategy. The buy-in that occurs at this level will be a large component of that will bring sustainability to the effort. If the board decides that certain goals must be delivered in a timeframe that cannot be supported by current industry experience, someone needs to “apply the brakes.” No matter how long it takes, waiting for the endorsement of leadership is vital.

The effectiveness of a corporate reliability strategy varies depending on:

- Leadership – who drives the initiative both from a corporate and business position

- Strategy – targeting what the business needs to survive

- Structure – including the “right” elements

- Culture – collaborating, focusing on defect elimination, and being proactive

- Talent – supporting its implementation

- Level of “buy-in” from participants – accepting the initiative from the board room to the production floor

- Competency – obtaining knowledge of practices

All these factors are important through this journey to achieving the business case targets. Hiring the leadership to take it forward is next.

Leadership Structure

Depending on whose “plate” this initiative is placed on, this individual must first ensure it is understood by both business leaders and functional leaders (e.g. vice president of engineering). The leadership structure and candidates should then be “installed.” This includes the global reliability leader and the regional reliability managers. The reporting roles are generally directly to the vice president of manufacturing with “dotted” lines to business management. For instance, the job description for the global reliability leader could be:

- Lead the development, implementation and management of the global reliability strategy.

- Past experience as a maintenance, reliability and site manager, preferably with multi-site experience

- Develop strategies to accelerate and improve current maintenance and reliability performance

- Ensure the appropriate metrics are in place

- Optimize the utilization of CMMS

- Drive asset care strategies

- Integrate reliability into capital projects with engineering

- Define and rollout plan for asset reliability issues

- Recruit, hire, and supervise reliability resources

- Support globally plant reliability improvement efforts

- Improve the company’s competency in reliability

- Drive risk out of fixed equipment with risk-based methods

Values and Policy

Prior to developing the strategy, certain other elements are needed, values, beliefs and policy. Values are what define corporate entities. They are the expectation to be achieved to meet the corporation’s mission. Values for reliability might be “achieve 95 percent uptime across all our production processes,” “elimination of failure will be our focus for all personnel,” or “work to eliminate all risks to our stakeholders from unplanned events.” Values should come from the senior leaders of the company and included in the reliability strategy. They are developed from value propositions that have been “sold” at the highest levels in the organization. Participants must believe in what can be delivered by improved reliability and what it means to their businesses.

Next comes the company’s beliefs. Just like safety beliefs like “all injuries are preventable,” reliability beliefs set the target for the culture. An example of a set of beliefs are:

- Equipment failures are preventable

- Reliability is everyone’s business

- Use the right tools

- Report all equipment issues

- Investigate abnormal conditions and failures

- Have visible metrics

- Management is committed to reliability

- Reliability issues are resolved

- Reliability is for the entire life cycle

- We use and follow instructions

Policies already exist for many facets of company operations such as safety, quality, ethics and environmental management to name a few. They reflect the current environment and can be changed. However, rarely does a company have a reliability policy. Reliability is often not communicated in terms that businesses understand and goals are rarely translated in policies. It would be surprising to have someone tell me what their reliability policy states.

The reliability policy should provide the business case for reliable equipment and the manufacturing process. It should include guidelines for maintenance and reliability, focus areas for improvement, a set of measures, and a time horizon to see the benefits of the effort.

For instance, a policy could open with, “Our production processes will operate without failure and will enable the extension of turnarounds to industry benchmarks.” Added to this expectation is, “We will focus our efforts on our largest volume production lines measuring our progress through asset utilization and mechanical availability targets with an expectation in two years to achieve 95 percent overall asset utilization and over 85 percent mechanical availability.” The policy can include objectives around recording downtime, and other practices to be implemented. The policy should provide the “what” but not the “how” to be effective.

Metrics are as important as the guidance itself. Initiatives that get measured get improved. Luckily, maintenance and reliability (like baseball) are full of statistics and easily measured. However, the trick is to develop the right mix of leading and lagging metric dashboards that will both inform senior management as to progress. They will connect with those on the production floor as to how they can “move the needle.” A few metrics should be used at a corporate level.

They should be well defined and their reporting be standardized so all sites collect them in the same way. These could include:

- Example #1: Operating Asset Utilization and $ Maintenance/RAV

- Example #2: MTBF and Downtime

- Example #3: MTBF, Downtime and Deviations (failures, upsets, non-conformances)

Finally, for this step, each site should know their starting place. An assessment should be performed across the network to determine the implementation level of maintenance and reliability practices for each site. The assessment can be facilitated by a third party or self-assessed by each site. There are many standard assessment tools to choose from and can be easily obtained.

Competency and Baselines

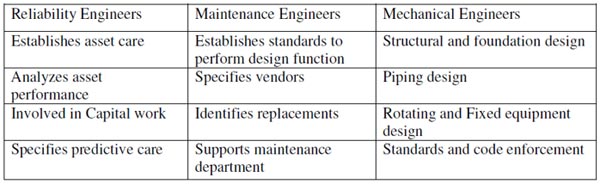

Organizations need to have individuals with the right competencies to carry out a corporate reliability strategy. It starts with hiring the right people with the right skill and knowledge sets. Job descriptions need to be modified and the used in the hiring process. Below is the distinction between reliability engineers and others involved in asset care.

In addition, to these skills, certification should be added as a prerequisite. Certifications like the Certified Maintenance and Reliability Professional (CMRP) should be an expectation for reliability engineers.

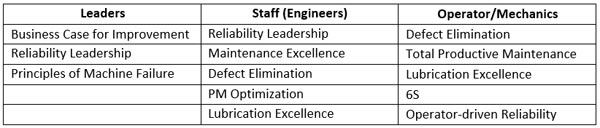

For those already in the organization, raising competency can be done through in-house training from either in-house staff or third-party organizations. The curriculum should vary based on where someone is in the organization. Below is an example of what could be offered:

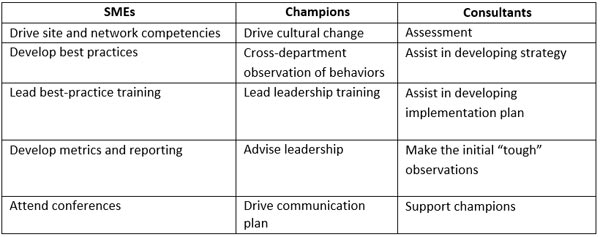

Finally, once people are trained and job descriptions modified, who does what needs to be answered. Among three groups — subject-matter experts, champions and consultants — each play a role in the implementation. Shown below is an example of how they can be used.

Reliability Program

It is important that companies considering a corporate reliability strategy rollout differentiate the various elements. Companies should first focus on values, beliefs, policies, and over-arching objectives for their plan. Vision and values define the corporation. They include the needs of the stakeholders, the approach to the marketplace, focus on EHS compliance, etc.

Beliefs are what the organization commits to in the initiative like:

- Equipment failures are preventable.

- Reliability is everyone’s business.

- Use the right tools.

- Report all equipment issues.

- Investigate abnormal conditions and failures.

- Have visible metrics.

- Management is committed to reliability.

- Reliability issues are resolved.

- Reliability is for the entire life cycle.

- We use and follow instructions.

Reliability policy is no different than those for safety, quality, ethics, and environmental plan deployment. They include the business case, guidelines for maintenance and reliability principles, criteria, and work practices (e.g. minimum expectations), focus areas for improvement (e.g. network uptime), measurement system to understand if progress is being made (e.g. asset utilization), and the time horizon for reliability improvement (e.g. 2 years).

The playbook encompasses principles, best practices, and procedures. Judgement is needed in the amount of detail provided in the playbook. It can be organized by various means like the five pillars from SMRP or by work process. SMEs and their networks can assist in their creation.

Under the strategy “loose and tight,” it is best to specify the principles and high-level practice expectations and leave the rest to the sites to decide how to implement these practices. Sites can get “turned off” by forcing practices on them from other sites that are believed to not have a “mature” level of practice. For instance, it is acceptable to specify that downtime needs to be understood, analyzed, and projects be developed to eliminate it but not to collect the information or who should do it.

This description for a critical equipment list does specify details of the practice to be implemented but does leave some “space” for sites to customize their approach.

Principle: Critical Equipment List

Critical equipment is equipment which merits more maintenance time and resources because of its value to the business. Identifying critical equipment within a production facility ensures equipment receives the proper amount of priority when determining allocation of resources. Critical equipment should be addressed before non-critical. (Note: The critical equipment list is not intended to fulfill any regulatory requirements, nor does it preclude or replace any HAZOP, MAPP or other safety studies.)

Practice

- All equipment within the production facility (including rotating and fixed equipment, structures, systems and other components (electrical, mechanical, instrumentation) has been evaluated and processed through the critical equipment evaluation.

- The critical equipment list is available and is used in establishing priorities for preventive maintenance activities, condition monitoring activities and spare parts inventory decisions.

- The critical equipment list is used to prioritize maintenance tasks.

- Failure of a piece of critical equipment triggers a detailed assessment of the failure, such as an RCA or RCM.

Being too prescriptive will run the risk of over-burdening sites that must make judgments on how far to implement a maintenance and reliability practice based on their size, resource levels, and business mission. It is best to provide the minimum level of practice and having each site decide its own course of action. Each should determine what is appropriate for its situation. As an example, larger sites with more resources can handle the expectations of a defect elimination process while smaller facilities might only perform root cause for failures that cause more than a day of downtime. Failure to “right-size” the initiative can result in “unfunded mandates” leading to the collapse of any attempt at implementation.

Finally, sharing knowledge of failures and fixes accelerates improvement. Fully utilizing the failure code functionality of the CMMS for all sites (what was observed, what failed, root cause, how it was fixed) is the first task. The triggers should establish what failures are tracked to root cause. A standard root cause tool across the network should be used to share root cause findings and actions to remediate similar situations at other sites.

Business and Site Implementation

The last step in our process to develop a corporate reliability strategy is to start the implementation. Each site will develop its own plan based on the gap between the corporate goals and their starting point established by their assessment. An accelerating factor to implementation is sharing. Sharing can begin with using SharePoint and intranet sites aimed at:

- “Quick win” communication

- Failure reporting (similar situation)

- Best-practice implementation

- Checklists

- Asking questions (“Has anyone seen….”)

- Corporate reliability procedures

- Site reliability procedures

- Requests for special parts and spares

- Metrics reporting

- Who’s who in maintenance and reliability

- Upcoming conferences and meeting

- Job announcements in maintenance and reliability

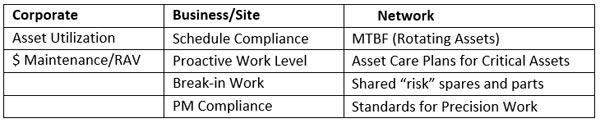

Metrics are vital to determining progress. As mentioned earlier only a few metrics are needed from a corporate perspective. Each site should use about 5-10 metrics that tie directly to the corporate metrics. Each network should be responsible for metrics that represent their activity which can then be leveraged across all sites The table blow provides an example.

Recognition is the “grease” that keeps the initiative moving forward. Multiple types of recognition are needed from the corporate to the site level. For instance, at the corporate level, publicized sites that achieved their corporate reliability targets should be publicized and corporate should sponsor internal networking meetings. At the business level they could sponsor CMRP certifications, award leaders throughout the organization that produce uptime and cost results, and sponsor incentives for the achievement of reliability goals. Sites can create a career track for reliability engineers, allow for conference attendance, and invite champions to participate in leadership roles.

What Is Out There?

Manufacturers with large installed capital bases and multiple manufacturing sites have established prescriptive reliability strategies. They occur in the oil and gas, food and beverage, discrete manufacturing industries and many government agencies. They can cover reliability practice usage from capital projects through to operations and maintenance activities. Some are very specific as to what is to be done during each phase of the life cycle of the asset.

Success and Pitfalls

So what separates the “good” programs that help from those that do not help the individual manufacturing site? Referenced earlier were the criteria of leadership, structure, culture, talent, and level of “buy-in” from participants. At the top of the list is leadership starting with the CEO and the board of directors. Whether the program is “top-down” or “bottom-up” driven has a lot to do with its success. Bottom-up initiatives have a small probability of success to succeed. Top-down initiatives get more attention, structure, funding, and scrutiny that drive their deployment. The scrutiny cascades across the entire organization and each business unit then deploys it to their needs. This deployment leads to the next important criteria, structure.

The right structure is vital to its effective deployment. It should be based on a “loose” and “tight” protocol. Driving too deep (being “tight”) into prescribing practices and methods will not allow site to develop “areas of excellence.” The “tight” structure should include company values along with a reliability policy. Some prescriptive high level guidance is acceptable such as requesting that downtime be recorded or the sites have a bad actor listing. It should be modeled after operating excellence outlined by organizations like Society of Maintenance and Reliability Professionals (SMRP) or other models from third-party subject matter experts.

Participant “buy-in” is a must. An effective deployment hinges upon individuals at the various sites becoming part of a network that focuses either on the entire initiative or one segment such as operator care, planning and scheduling, or defect elimination, etc. This is where the “loose” part of the deployment strategy is best leveraged. Those that feel ownership can take the initiative further than any senior leader sitting in the corporate headquarters.

The other factors that can doom a corporate reliability strategy are focusing on cost, not having the right talent in place to both lead and deploy the program, forcing “one size fits all plants” with requirements for best practice implementation, not recognizing that a minimum of two years is needed to see improvement, and forgetting to include the operations and engineering groups as partners with maintenance in its deployment.

The article discussed how to build a corporate reliability strategy. Based on the criteria, structure, leadership, culture, talent, and level of “buy-in” a corporate reliability strategy can drive the achievement of corporate and business goals. A process was provided that detailed five steps for its creation. The first step builds the business case. Buy-in to its goals and objectives must occur from the board of directors all the way down to those who operate and maintain the equipment. The second step builds the structure which is important to its deployment. The third step builds the competencies and skills required to develop the right talent to be in place to build the company’s competency in maintenance and reliability.

The fourth step builds the playbook that encompasses the principles, practices, and procedures to be used. The right “mix” of guidance and prescribed practices is vital to both provide the expectations of the initiative but to also leverage local pockets of excellence at various sites. The final step is to start the implementation by completing demonstration projects, sharing successes, establishing networks recognizing achievement, and holding business and corporate meetings to review progress. Overall, the absence of corporate reliability guidance can be detrimental to achieving a predictable supply chain since the response to maintenance and reliability issues is not defined.

We previously published this article in the Reliable Plant 2016 Conference Proceedings.

By David A. Rosenthal, PE, CMRP, Reliability Strategy and Implementation Consultancy LLC